When the internet crept slowly in to our consciousness in the middle of the 1990s, its world of bits delighted us with its promise to free us from the tyranny of atoms.

In particular, it delighted those of us with a bent toward intellectual career pursuits rather than manual labour – for, the digital world is the ultimate playground in which to develop and profit from intangible effort.

Many of our cultural industries are now on the cusp of completing the great digital migration of the last 20 years. But, in the final chapter of this revolution, I sense a counter-movement – a yearning for tangible engagement that can only be achieved through the tactile experiences digital content have eradicated. We’re going back to the future.

You can see it in photography, where users of Instagram and its imitators take pains to apply imperfection filters that resituate their subjects back in the 1970s.

And you see it in all the new ways that digital photographers have to solidify their ephemeral snaps in the old world – like Stickygram’s Instagram fridge magnets, or Instagrams printed on to 35mm slide films for the Projecteo projector.

The trend cuts across content industries. Just as music single purchases are nearing becoming entirely digital, the most analogue format of all is recoiling – UK vinyl sales have boomed in step with MP3s’, and doubled this year for Amazon.

This counter-intuition is actually catharsis. Just as information supposedly “wants to be free“, in an age awash with digital, many of us, it transpires, also want it to be locked in familiar physical form.

But this yearning is not just nostalgia from those with long enough memories to reconstruct the past. Those guiltiest of the trend are the young. Never having known a time during which content was made from anything other than invisible bits and bytes, many in their teens and early 20s are turning their backs on their own, digitally voluminous era.

Their embrace of board games, film cameras and LPs is curious in the truest sense. This is novelty escapism, just like the cycle of retro music, youngsters’ current fad for which is 90s – also, coincidentally, the decade that divides our analogue history from our digital present.

“There seems to be an over-supply of pure digital products,” Projecteo maker Mint Digital’s co-founder Tim Morgan told me. “But consumers crave context and something they can hold in their hand.”

Is it just me or has digital innovation slowed down lately? In his book You Are Not A Gadget, technology critic Jaron Lanier admonishes our supposedly navel-gazing social web generation for having simply invented “trivial mash-ups of the culture that existed before”. Our digital migration has has stripped away many of the artefacts that help define us – books, gone from our shelves; music and movies, long ago sent to landfill; photographs, now taken, instantly shared and quickly forgotten. But in their place are digital replacements of the old formats, not necessarily new forms.

So much are some replicas imitations, it’s no wonder consumers are returning to the originals – this application which reconstitutes a child’s paint pot and paper as a £1,000 PC setup especially dismayed me. Yet the technology industry congratulates itself for such transference of atoms to bits with equivalence, not improvement.

For the last 20 years, this digital intangibility was a proxy for technology innovation generally; the web seemed to be the driving force of all advances. Now it feels like the fundamental tenets of our networked digital landscape are largely set in place. But a host of very tangible digital innovations promises to restore forward momentum…

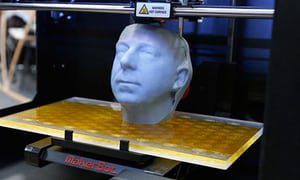

3D printing is going to revolutionise manufacture, throwing everyone’s focus on to real, physical products. Pretty soon, people will marvel at taking models of household objects on a USB stick to a 3D printing shop, while repatriation of off-shored manufacture from Asia to local 3D printing depots could reshape global politics.

The renewed craze for home electronics hacking – mimicking the homebrew computer clubs of the 70s that gave rise to the PC revolution we all now take for granted – is unleashing all manner of new devices and creativity.

And the coming accessibility of simplified smart home technologies and the promise of internet-connected objects everywhere will sunset the notion of an intangible web behind an LCD screen.

This is a revolution that starts with recognising mobile and wearable devices – physicality and not virtuality – are the prime factors moving the industry already today. What comes next looks plenty more exciting, and will make an animated-cat .gif flipbook – digital content remanifested as analogue once more – look like a waste of innovation.

All this will change the demands on companies and their employees. Tomorrow, the hot skillsets may not be web development and social media marketing but engineering, product design and electronics.

Once the fact that, yes, we can all now talk to each other using social media becomes no longer a novelty, it is these new technologies that touch us like the old which will truly command our wonder, evoking a deep but forgotten familiarity.

For, in a world dominated by bits, atoms are due a comeback.