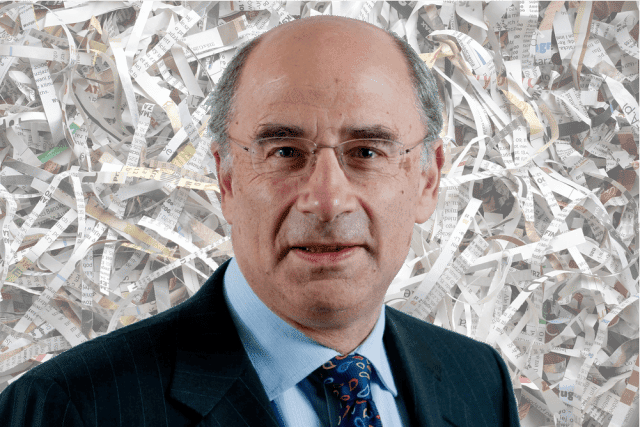

The big Leveson inquiry that has corruscated UK journalism standards discredits itself by refusing to accept that weblogs or social media can be news vehicles and by wrapping itself in digital contradictions.

But technology platforms and digital libertarians alike should rejoice at, not feel affronted by, the report’s ignorance — for, it seems to recommend specific new regulation only for that waning group of large publishers who print newspapers.

For an inquiry that was tasked by government to examine the “press”, this focus is perhaps unsurprising. But Leveson’s intellectual contortions, in exploring news publishers’ online evolution, are curious, and important in assessing where UK media policy currently lays…

Newspapers better than the internet

Leveson’s 1,987-page report appears to rule out out extending proposed new self-regulation to online-only publications and has rejected newspaper publishers’ argument that they should be allowed to re-publish whatever is online — on the basis of a fundamental value judgement…

“The internet does not claim to operate by any particular ethical standards, still less high ones. Some have called it a ‘wild west’ but I would prefer to use the term ‘ethical vacuum’.

“This is not to say for one moment that everything on the internet is therefore unethical. That would be a gross mischaracterisation of the work of very many bloggers and websites which should rightly and fairly be characterised as valuable and professional. (But) bloggers and others may, if they choose, act with impunity.

“The press, on the other hand, does claim to operate by and adhere to an ethical code of conduct. People will not assume that what they read on the internet is trustworthy or that it carries any particular assurance or accuracy; it need be no more than one person’s view. There is none of the notional imprimatur or kitemark which comes from being the publisher of a respected broadsheet or, in its different style, an equally respected mass circulation tabloid.”

The irony of this viewpoint is that it is nostalgic. Leveson has admonished newspaper publishers for dropping standards. Some, though not all, have hacked the mobile phones of a murdered schoolgirl and terrorism victim, chased celebrities down the street for photographs and too commonly disregard accuracy and right of reply, the report found. Leveson concluded newspaper publishers have “caused hardship”, “wreaked havoc” with the lives of innocents and failed to live up to their responsibilities.

Yet he still holds these newspapers to meet higher standards than he expects of the internet.

Print is the focus

Lord Justice Leveson has proposed a revised and enhanced self-regulation body to oversee UK “press” standards. But he is not going so far as to lay down the terms or specific scope of that body. The current Press Complaints Commission (PCC), comprised of big newspaper editors, encompasses newspapers and their websites, but it is thought its now-discredited code is subscribed to by only one online-only outlet – AOL’s Huffington Post UK.

In handing over the establishment of the new body, Leveson is passing on whether that scope should be extended farther online — but the clear cue from his report is that new-look self-regulation should remain pertaining to newspapers and their own sites. That is because he is both satisfied that some areas of online media have necessary protections built in — and because he is frankly uncertain whether online media can be controlled anyway…

Internet is uncontrolled, except when it is

Leveson himself notes “profound questions about the ability of any single jurisdiction to set standards which, in a free and open society, can be breached online with the click of a mouse”, and says: “In evidence to the Inquiry, the Internet has been described as an unregulated space, in which businesses can avoid the regulation of a given jurisdiction by hosting the content they publish in a different legal jurisdiction.

In one breath, he disagrees, calling that view “a simplification that ignores what is a more complex picture”, before reeling off a list of bodies and laws to show the internet is indeed already regulated. However, later in the report, he contradicts himself, asserting: “The internet is an uncontrolled space.”

The contradiction is tangible. It shows Leveson wrestling not just with whether digital news outlets should be self-regulated in the same way proposed of newspaper websites, but whether they can. For these two reasons, Leveson’s conclusion appears to be that the internet must inevitably host lower-quality content than must be expected of print publishers.