The album is dead, long live the playlist – the new primary container unit of music consumption.

iTunes Store’s disaggregation of the album in to its individual parts long ago allowed listeners to reassemble those parts to their own, not artists’, preference.

In fact, there is no more apt an emblem for how our generation can now curate and remix content of all kinds for itself than the music playlist.

It is the emotional currency of this construct which music services like Spotify hope to tap to drive up consumption. By enticing users to invest in creating dozens of personalised playlists, which cannot be exported to rival services, Spotify hopes listeners will ascribe to it enough value that it becomes difficult to leave its ecosystem.

It is the emotional currency of this construct which music services like Spotify hope to tap to drive up consumption. By enticing users to invest in creating dozens of personalised playlists, which cannot be exported to rival services, Spotify hopes listeners will ascribe to it enough value that it becomes difficult to leave its ecosystem.

It appears to be working. CEO Daniel Ek recently said Spotify users have created more than 700 million playlists, websites like ShareMyPlaylists exist to list thousands of them and Spotify’s in-app search results now also return users’ playlists.

But is this playlist-centric music universe pre-destined to be the best means of consumption today and going forward?

I’m declaring Spotify playlist bankruptcy. Now up to 102 playlists after three years, my Spotify is exceeding its ability to organise my music.

The problem is, Spotify considers the playlist the primary and virtually only organising structure for the music I play. Yet much of that music defies such suitable description…

In Spotify, playlists are not just a custom means to structure a mixture of tracks assembled by myself or others, like mixtapes of old – they have also become the pretty much only way to easily bookmark a favourite album for future playback. When I want to shelve such albums – let’s say, R.E.M.’s Reckoning or The Decemberists’ The King Is Dead – for later, I have to create a “playlist” to house their contents.

In Spotify, playlists are not just a custom means to structure a mixture of tracks assembled by myself or others, like mixtapes of old – they have also become the pretty much only way to easily bookmark a favourite album for future playback. When I want to shelve such albums – let’s say, R.E.M.’s Reckoning or The Decemberists’ The King Is Dead – for later, I have to create a “playlist” to house their contents.

That’s an anachronism. The result is, my Spotify application contains both structures that I consider playlists (curated selections, for particular moods or periods) and structures that Spotify considers playlists but which I consider albums.

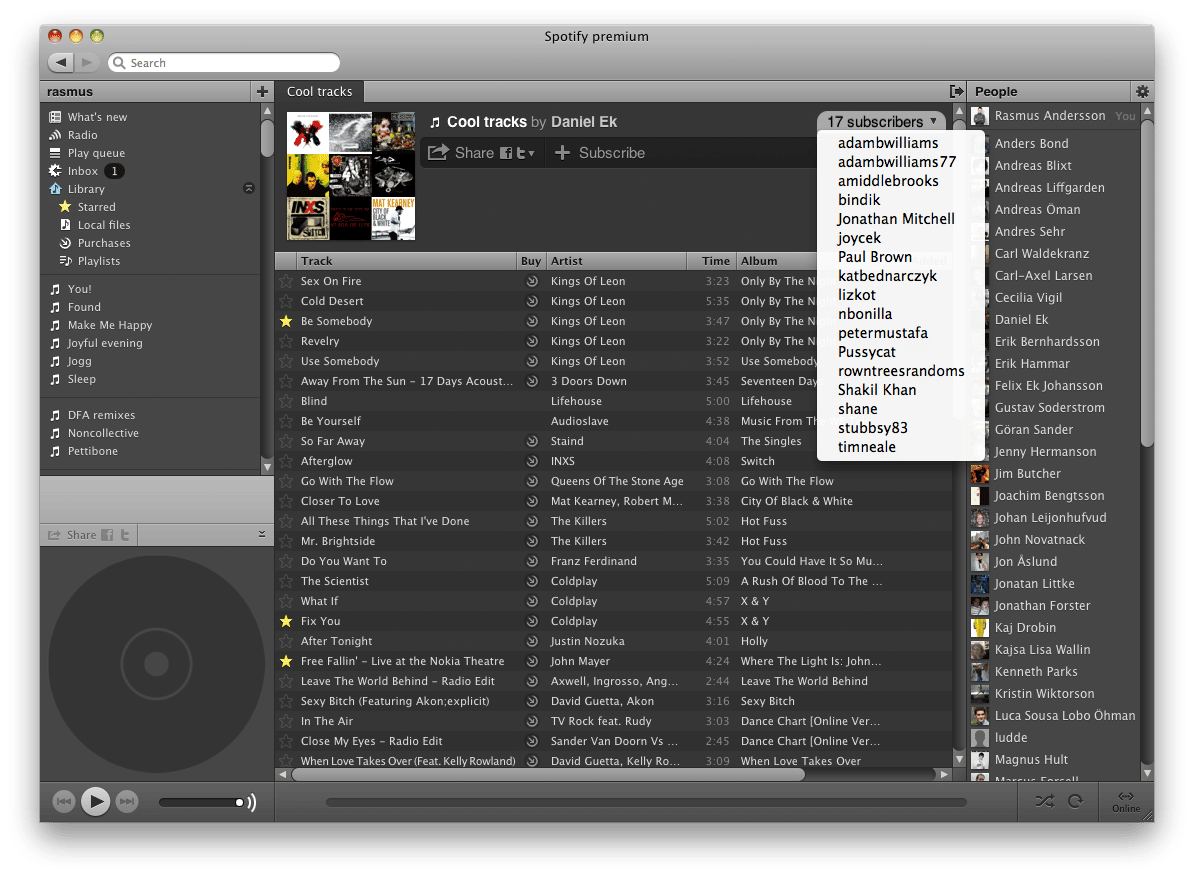

There they sit – in one long, unwieldy list – on the left side of the app window, beneath a new array of dozens of Spotify’s in-app apps. They cannot be separated from each other nor nested within each other. I can no longer distinguish the music I have programmed for particular occasions, like house parties, from some of the classic collections that I love so much because of their artists’ composition, not mine.

Sure, Spotify’s Library provides a centralised location for all the music I have starred – albums included. But they nestle together with all the individual tracks I have ever starred or placed in a mix playlist – album collections are lost among my Library’s 2,458 listed tracks.

Three years after adding music to Spotify, the application is the best route to a universe of millions of tracks. But it is beginning to out-do its own capacity just to help me find the music I have loved along the way. The more I use Spotify, the more chronic the issue is likely to become.

Three years after adding music to Spotify, the application is the best route to a universe of millions of tracks. But it is beginning to out-do its own capacity just to help me find the music I have loved along the way. The more I use Spotify, the more chronic the issue is likely to become.

Perhaps I am simply from a time before today’s generation, which supposedly wants to curate everything for itself. I often do that, too; it’s one of the main reasons I use Spotify. I’m ready to ditch my CD collection. But that would be more palatable if Spotify had a more intuitive language for expressing my cloud-based equivalents. Spotify should not overestimate society’s preference for personalised playlists over already-curated cultural units.

I call for one simple thing – the addition of a navigation architecture that more visibly represents the album. This would not undermine Spotify’s playlistcentricity; albums would still exist as, essentially, “album playlists”. But they should be distinct from mix playlists. I seek an in-app “shelf” to which I can drag my favourite collections.

The new wave of subscription content access services in all media – music, movies, TV and more – should remember that, if they become successful, they may need to scale their interfaces as well as their businesses. Else, consumers may become lost in a sea of choice.