CARDIFF, Wales – Michelle Teran is the pied piper of wireless networks. Leading a band of followers through the city streets, the Canadian artist drags along a screen embedded in a suitcase that is showing supposedly secret images captured from cameras inside surrounding buildings.

Call it war-driving for video. Although many people assume new surveillance technology that lets cameras transmit footage wirelessly to TVs and computers is private, Teran is on a mission to show them otherwise.

Equipment that underpins in-store closed-circuit TV cameras, personal internet surveillance, even baby crib monitors and TV signal extenders, sends signals along the 2.4-GHz wave band, an unlicensed portion of radio spectrum that is firmly in the public domain. If the cameras are set up incorrectly, passersby with the proper equipment can easily grab images from them when they wander within range.

Concealing a scanner and microphone under a thick black coat for a performance art project that turns surveillance inside out, Teran silently pounds the sidewalks searching for these invisible scraps — and shows them to a gathering public band of spectators.

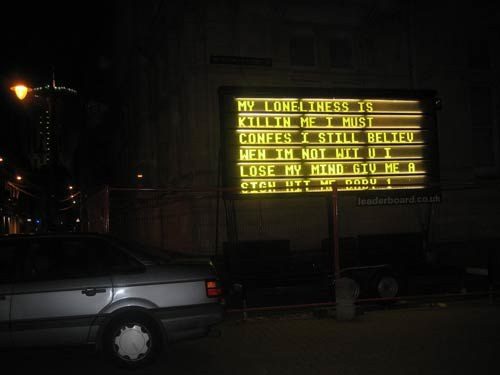

Michelle Teran rebroadcasts closed-circuit TV footage of the scene after a hotel collapse to interested passersby. ROBERT ANDREWS

“People don’t really understand the technologies they’re using,” she said. “They are setting this up and (unwittingly) becoming broadcasters.

“There are these technological borderline situations. On the one hand, you have this boundary that the person sets up and, on the other hand, you have this boundary that is set up by the range of the radio signal, so you have a restructuring of the geography of the city because of radio propagation.”

Since the 2.4-GHz frequency was made license-exempt, it has attracted communications from all manner of devices, including game console controllers, cordless telephones, Bluetooth gadgets, microwave ovens and, increasingly, cameras that beam security pictures to a home PC for remote viewing over the web. Equipment frequently carries a range of about 100 feet, makers say.

Toronto-based Teran has performed her work, Life: A User’s Manual, in cities around Europe, using reception equipment she said was common and affordable to all, but which she refused to name specifically.

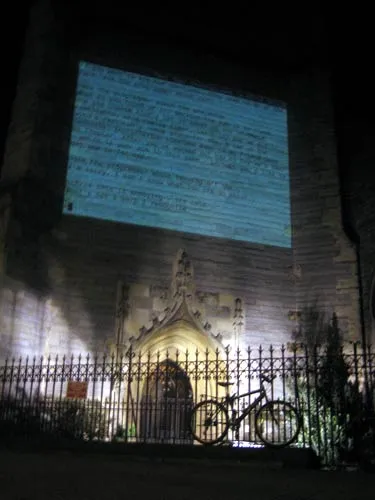

A nighttime text-adventure game is projected onto a church at the Festival of Creative Technology. ROBERT ANDREWS

Giving the latest enactment for May You Live in Interesting Times, Cardiff’s inaugural Festival of Creative Technology this past weekend, she remixed the images that bleed through walls and over the psychological boundary between private and public.

Attracting bemusement and catcalls as she tuned her equipment in search of signals, Teran first showed her tag-along audience pictures from an aerial CCTV camera capturing the scene after a city hotel collapsed, and was then verbally abused by a bar owner who objected to his punters being shown footage of themselves under surveillance. “Puzzlement, amusement, disorientation, surprise” are normal reactions, she said, adding that law-enforcement cameras are usually secured.

“People are feeling insecure, but their security equipment gives only an illusion of protection,” Teran said. “It’s just something that comes in a box and they pick it up but they don’t really understand how their contribution is affecting the city. I like the idea of people transmitting their personal narratives that are overlays of the city, these invisible stories. The camera starts to create a story about the person who has it and where they’re placed within the city.

“I see the same scenes over and over again; the camera is watching daily banalities, maybe something that is a private moment that maybe I shouldn’t be watching. For example, a son had set up a camera for his elderly mother just to make sure that she doesn’t fall, and I was able to see her sitting up and calling to him. Am I invading somebody’s private space or are they coming into mine?”

Not enough wireless equipment offers encryption, and users often don’t switch on encryption features that are included in their devices, according to John Wilson, a wireless communications consultant present at May You Live in Interesting Times.

“The default setting in the hardware may leave their connection open,” he said. “There is an explosion of art projects using wireless — ‘locative media’ is a buzzword — a lot of it is banal, fetishizing GPS technologies, whereas locative-media aspirations originally emanated from the 3G operators.”

The festival brought together artists and technologists exploring location-based art and gaming. In citywide experiments, attendees used SMS messaging to play a nighttime text-adventure game projected onto a church, heard conference speeches on using satellite tracking to visualize the “poetry” of incoming tides, and were dropped into a 3-D game representation of the city in which players must evade opponents in the real Cardiff whose wearable GPS handsets linked them to the virtual environment.

“Michelle’s performances create a space that echoed the general theme of the festival — making the gap between art and technology slightly more accessible,” said festival director Gordon Dalton. “The festival raised issues that were not only pertinent to an academic audience but also provided some interface with the wider general public.”